I’ve been a paramedic for eight years. I’ve seen blood, guts, screaming families, death. Nothing shakes me anymore.

But yesterday broke me.

We got a call for a cardiac arrest at a strip mall. Routine. My partner, Wayne, drove. We’d been working together for three years. Solid guy. Never hesitated. Never froze.

We pulled up. A crowd gathered around a collapsed man in his fifties. I grabbed the kit. Wayne grabbed the stretcher.

I knelt down, started compressions. “Sir, can you hear me?” No response. Weak pulse. We had maybe two minutes.

“Wayne, get the oxygen!”

He didn’t move.

I looked up. He was staring at the man’s face, his own face turning white.

“Wayne!”

“I’m not touching him,” Wayne said, his voice shaking.

“What?” I thought I heard him wrong. “He’s dying!”

“I know who he is.”

I kept doing compressions. “I don’t care if he owes you money, we have a job to – ”

“He killed my daughter.”

I froze for half a second. The man’s pulse was fading.

“Wayne, you can hate him after we save him. Help me now!”

Wayne dropped the oxygen tank. It clanged on the pavement. He walked back to the ambulance.

I couldn’t do this alone. The bystanders were useless. I called for backup, but they were fifteen minutes out.

The man’s lips were turning blue.

I did everything I could. Alone. Chest compressions until my arms burned. Mouth-to-mouth. The defibrillator. Nothing.

He died on that sidewalk.

When backup arrived, they found me sitting there, covered in sweat, shaking. Wayne was in the driver’s seat, staring straight ahead.

I reported him. Of course I did. He abandoned a patient. That’s the line.

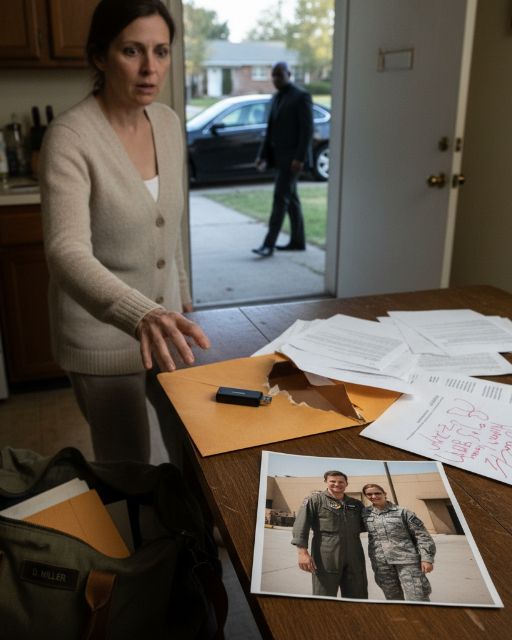

Two days later, I got a letter in my mailbox. No return address. Just a newspaper clipping from six years ago.

“Local Man Walks Free After Daughter’s Hit-and-Run Death – Technicality Lets DUI Driver Escape Justice.”

There was a photo. The man from the sidewalk. Smiling in a suit outside a courthouse.

And next to him, a photo of Wayne holding a little girl in a pink dress.

I realized Wayne wasn’t in the driver’s seat that day because he was a coward.

He was in the driver’s seat because if he’d stayed, he would have done something much, much worse than nothing.

My hands trembled as I held the brittle piece of newsprint. The smiling face of the man, Arthur Harrison, seemed to mock me from the page. The little girl in Wayne’s arms had a bright, gap-toothed grin. Her name was Lily.

I suddenly felt sick to my stomach. I had reported my partner. I had followed the rules, stuck to the code.

But the code didn’t account for this. It didn’t have a protocol for staring into the face of the man who destroyed your world.

My report was already filed. The wheels were in motion. Wayne was suspended, pending an investigation that would almost certainly end his career. A career he loved, a career he was damn good at.

I had put the final nail in his professional coffin.

The guilt was a physical weight. It sat on my chest, making it hard to breathe. I thought about Wayne, sitting in that ambulance, his knuckles white on the steering wheel. He wasn’t just staring ahead. He was holding himself together. He was choosing inaction over an action that would have landed him in prison.

The next few days were a blur of sleepless nights and hollow hours at the station. Everyone was walking on eggshells around me. They knew Wayne had been suspended, and they knew I was the one who made the call. I could feel their judgment, their whispers when I walked by.

Did they think I was a snitch? A by-the-book robot with no heart?

Maybe I was.

I was called into a meeting with our supervisor, a stern woman named Captain Davis. She had my report on her desk.

“Robert,” she said, her voice even. “Walk me through it again.”

I did. I recounted the events exactly as they happened, my voice sounding distant and clinical even to my own ears. The call, the arrival, the compressions, Wayne’s refusal.

“He said the man killed his daughter,” I finished, my voice barely a whisper.

Captain Davis steepled her fingers, her gaze unblinking. “I’m aware of Wayne’s history. It’s in his file. But it doesn’t change the facts. He abandoned a patient.”

“He wasn’t in his right mind,” I argued, hearing the desperation in my own voice. “You can’t expect someone to be rational in that situation.”

“I expect them to be a paramedic,” she said coolly. “That’s the job. We don’t get to choose.”

She was right, of course. From a professional standpoint, she was one hundred percent right. But my gut screamed that she was wrong.

I left her office feeling emptier than before. The system was going to chew Wayne up and spit him out, and I had handed him to it on a silver platter. I couldn’t let it go. I needed to understand more than what a six-year-old newspaper clipping could tell me.

That night, I went home and fell down a rabbit hole on the internet. I searched for “Arthur Harrison” and “Lily Miller.”

The articles told the story. Wayne’s daughter, Lily, seven years old, had been riding her bike on the sidewalk just a few houses down from her own. A car had swerved off the road, hit her, and kept going.

Arthur Harrison was arrested two days later. His car had damage consistent with the accident. He had a history of DUIs. It seemed like an open-and-shut case.

But it wasn’t. The key witness, a neighbor, gave a shaky description of the driver. The timeline was fuzzy. Harrison’s lawyer was a shark, and he picked the prosecution’s case apart piece by piece. The technicality mentioned in the clipping was a botched chain of custody for the blood alcohol test. It was thrown out.

Without the DUI charge, the case crumbled. Harrison walked.

I felt a fresh wave of rage on Wayne’s behalf. The injustice was sickening. But there was something else, a small, nagging detail that I couldn’t shake. All the articles mentioned Harrison’s complete lack of remorse during the trial. He was described as “stoic,” “unemotional,” and “arrogant.”

That didn’t line up with the man I’d seen on the sidewalk. His face, in those final moments before he collapsed, wasn’t arrogant. It looked tired. Haunted.

I kept digging. I found Harrison’s home address from an old public record. It was on the other side of town, in a quiet, unassuming suburb.

I didn’t know what I was doing. What was I going to do, knock on the door of a dead man’s house? Confront his grieving family?

The next day, I found myself driving there anyway. I parked my car down the street from a modest, well-kept brick house with a tidy garden out front. I sat there for almost an hour, my engine off, just watching.

Finally, I got out and walked up the stone path. My heart was pounding. This was a terrible idea. A massive, career-ending, life-ruining idea.

I rang the doorbell.

The door was opened by a woman in her fifties with tired, kind eyes swollen from crying. She wore a simple black dress. This had to be his wife, his widow.

“Yes?” she said, her voice soft.

“Mrs. Harrison?” I stammered, my prepared speech dissolving in my throat. “My name is Robert. I… I was one of the paramedics.”

Her expression softened with a flicker of recognition. “Oh. Oh, of course. Please, come in.”

I stepped into a home that felt heavy with grief. Photographs lined the mantlepiece. Arthur Harrison with his wife on a beach, smiling. Arthur with a young man who shared his features.

“That’s our son, Thomas,” she said, following my gaze. “He’s at the university. He’s driving home now.”

Her name was Eleanor. She offered me a seat and a glass of water, her movements graceful despite her obvious sorrow. She thought I was there to offer my condolences, to tell her we did everything we could.

“I’m so sorry for your loss,” I said, the words feeling inadequate and false.

“Thank you,” she said, sitting opposite me. “It was his heart. The doctors had been warning him for years. The stress…” She trailed off, dabbing her eyes with a tissue. “He was never the same after the accident.”

I tensed. “The accident?”

A shadow passed over her face. “The one with the little girl. Six years ago.” She looked at me, her eyes pleading for understanding. “My husband was not a monster. He was a good man who made a catastrophic mistake.”

She told me that the man portrayed in the papers wasn’t the real Arthur. She said he was consumed by guilt. He’d lost his job, his friends. He barely left the house.

“He started a foundation, you know,” she said quietly. “Anonymously. He donated almost everything we had to a fund for families of hit-and-run victims. It was his penance.”

This was not the man from the newspaper. This was a man tormented by his past, slowly dying from the weight of it.

I felt my certainty begin to fracture. The world wasn’t black and white anymore. It was a murky, confusing gray.

Just then, the front door opened. A young man in his early twenties walked in, dropping a set of keys on the hall table. He had his father’s dark hair, but his eyes were filled with a raw, youthful anxiety.

“Mom?” he said. “I came as fast as I could.”

“Thomas, this is Robert,” Eleanor said. “He was one of the paramedics who tried to help your father.”

Thomas looked at me, and in his eyes, I saw it. It wasn’t just grief. It was fear. A deep, panicked terror that I’d seen a thousand times in the faces of people at accident scenes. The look of someone who knows they are to blame.

And suddenly, I knew. It was a gut feeling, an instinct honed by years of walking into chaotic situations and having to read people in an instant.

“Thomas was with his father that night,” Eleanor added, oblivious. “It was a terrible, terrible time for our family.”

The pieces clicked into place with a horrifying certainty. The shaky witness description. The stoic, unemotional defendant. The father who would do anything to protect his son.

Arthur Harrison didn’t kill Lily Miller.

He was in the passenger seat.

His sixteen-year-old son, Thomas, was the one behind the wheel.

Arthur had taken the fall. He had sacrificed his reputation, his career, his entire life, to save his son from the consequences of one horrific, youthful mistake. He played the part of the unremorseful monster to protect his boy. And the stress of that lie, the weight of that guilt, had finally killed him.

I mumbled my apologies and left the house in a daze. I drove, not to my own apartment, but to Wayne’s. I had to tell him. He deserved to know the truth. All of it.

I found him sitting on his porch, staring into the distance. He looked like he’d aged ten years. He was unshaven, his eyes were bloodshot, and an empty bottle sat by his chair.

“Go away, Robert,” he said without looking at me. “Come to gloat?”

“No,” I said, sitting down next to him. “Wayne, we need to talk. About Arthur Harrison.”

He flinched at the name. “There’s nothing to talk about. The bastard’s dead. I hope he’s rotting.”

“He wasn’t the one driving the car, Wayne.”

Wayne turned to look at me then, his eyes filled with a mixture of confusion and contempt. “What are you talking about? Of course he was.”

I told him everything. My visit to the house. My conversation with Eleanor. The look in his son’s eyes. The anonymous foundation. The slow, six-year decay of a man living a lie to protect his child.

As I spoke, the anger drained from Wayne’s face. It wasn’t replaced by relief, or satisfaction. It was replaced by a profound, bottomless emptiness. For six years, his grief and his rage had a target. A single, monstrous face he could hate.

Now, that target was gone.

He was left with the image of a scared teenager and a father who made a terrible choice out of love—a motive that Wayne, as a father himself, could understand with agonizing clarity.

“His son…” Wayne whispered, the words catching in his throat. “It was his son?”

I just nodded.

Wayne put his head in his hands and began to sob. They weren’t angry tears. They were the tears of a man whose entire foundation had just crumbled beneath him. The hate had been an anchor in his sea of grief. Now he was just adrift.

We sat there for a long time, in silence. The next steps were a minefield. What could we even do? The boy, Thomas, was an adult now. The statute of limitations was likely up. There was no legal justice to be had.

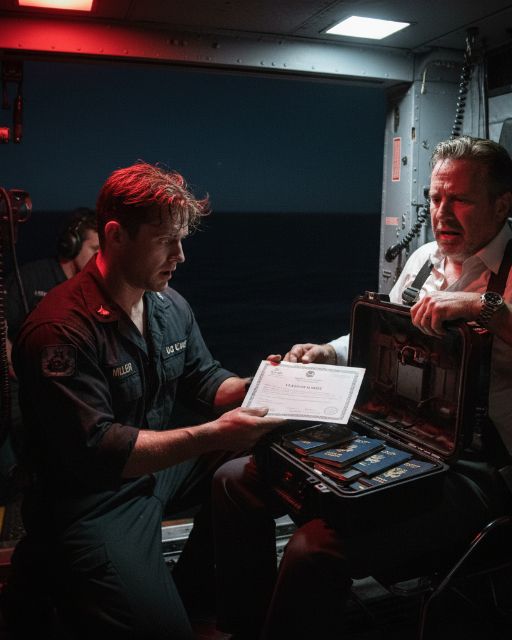

A week later, Wayne’s hearing was held. I testified on his behalf. I told the board about the clipping, about the shock, about the impossible situation he was in. I told them he wasn’t a bad paramedic; he was a grieving father who broke. My testimony, combined with his clean record, saved his job. He was given a six-month leave and mandated therapy.

But we both knew it wasn’t over.

A few weeks after that, Wayne called me. His voice was different. Calmer.

“I want to meet him,” he said. “The son. Thomas.”

My blood ran cold. “Wayne, I don’t think that’s a good idea.”

“I’m not going to yell at him,” he said. “I’m not going to hurt him. I just… I need to.”

I agreed to go with him. I called Eleanor and explained, as gently as I could, that Wayne knew the truth and wanted to speak with Thomas. She was hesitant, but she agreed.

We went back to that quiet brick house. Thomas was waiting for us in the living room, pale and trembling. He looked like a frightened child.

Wayne sat down on the sofa across from him. He didn’t look angry. He just looked tired. Sad.

He didn’t start with accusations. He started by talking about Lily.

“She had this little laugh,” Wayne began, his voice thick with emotion. “It sounded like tiny bells. She was afraid of spiders but loved worms. She wanted to be an astronaut, but she also wanted to be a ballerina. She thought she could do both.”

He pulled a worn photo from his wallet and slid it across the coffee table. It was the same one from the news clipping. Lily, in her pink dress, beaming at the camera.

Thomas stared at the photo, and his composure shattered. A strangled sob escaped his lips, and then he was weeping, his body shaking with the force of six years of buried guilt.

“I’m so sorry,” he choked out between sobs. “I never saw her. It was getting dark. I was sending a text. I just… I panicked. My dad… he made me switch seats before anyone came. He said my life would be over.”

Wayne just listened. He let the boy’s confession fill the quiet room.

When Thomas was finished, Wayne looked at him, his eyes filled not with hatred, but with a deep, aching sorrow.

“Your father gave up his life to save yours,” Wayne said softly. “Don’t waste it.”

That was it. There was no shouting. No demands for justice. Just the quiet, devastating weight of the truth.

We left soon after. As we walked to the car, Wayne seemed lighter. The burning rage that had consumed him for years had been extinguished, replaced by a painful, but clean, sadness.

It wasn’t forgiveness. Not yet. Maybe not ever. It was something more complicated. It was an acknowledgment of a shared, terrible humanity. A recognition that monsters are rarely as simple as we want them to be, and that sometimes, the most destructive acts are born from love.

The real lesson wasn’t learned on that sidewalk next to a dying man. It was learned in a quiet living room, watching two broken souls confront the ghost that had haunted them both. I learned that our job isn’t just about saving lives; it’s about navigating the wreckage when we can’t. And I learned that hate is a prison. It locks you in a cell with the very thing that hurt you. The only way out is to find the courage to turn the key, even if you don’t know what’s waiting on the other side.